Humans (and most animals) digest all their food extracellularly; that is, outside of cells.

- Digestive enzymes are secreted from cells lining the inner surfaces of various exocrine glands.

- The enzymes hydrolyze the macromolecules in food into small, soluble molecules that can be

- absorbed into cells.

The diagram shows the major topological relationships in the body. The linings of all

The diagram shows the major topological relationships in the body. The linings of all

- exocrine glands, including digestive glands,

- nasal passages, trachea, and lungs,

- kidney tubules, collecting ducts, and bladder,

- reproductive structures like the vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes

are all continuous with the surface of the body.

Anything placed within their lumen is, strictly speaking, outside the body. This includes

- the secretions of all exocrine glands (in contrast to the secretions of endocrine glands, which are deposited in the blood).

- Any indigestible material placed in the mouth which will appear, in due course, at the other end.

Food placed in the mouth is

Food placed in the mouth is

- ground into finer particles by the teeth,

- moistened and lubricated by saliva (secreted by three pairs of salivary glands)

- small amounts of starch are digested by the amylase present in saliva

- the resulting bolus of food is swallowed into the esophagus and

- carried by peristalsis to the stomach.

The wall of the stomach is lined with millions of gastric glands, which together secrete 400–800 ml of gastric juice at each meal.

Several kinds of cells are found in the gastric glands

Parietal cells secrete

- hydrochloric acid

- intrinsic factor

Parietal cells contain a H+/K+ ATPase. This transmembrane protein secretes H+ ions (protons) by active transport, using the energy of ATP. The concentration of H+ in the gastric juice can be as high as 0.15 M, giving gastric juice a pH somewhat less than 1. With a concentration of H+ within these cells of only about 4 x 10-8 M, this example of active transport produces more than a million-fold increase in concentration. No wonder that these cells are stuffed with mitochondria and are extravagant consumers of energy.

Intrinsic factor is a protein that binds ingested vitamin B12 and enables it to be absorbed by the intestine. A deficiency of intrinsic factor — as a result of an autoimmune attack against parietal cells — causes pernicious anemia.

The chief cells synthesize and secrete pepsinogen, the precursor to the proteolytic enzyme pepsin.

Pepsin cleaves peptide bonds, favoring those on the C-terminal side of tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan residues. Its action breaks long polypeptide chains into shorter lengths.

Secretion by the gastric glands is stimulated by the hormone gastrin. Gastrin is released by endocrine cells in the stomach in response to the arrival of food.

Absorption in the stomach

Very little occurs. However, some water, certain ions, and such drugs as aspirin and ethanol are absorbed from the stomach into the blood (accounting for the quick relief of a headache after swallowing aspirin and the rapid appearance of ethanol in the blood after drinking alcohol).

As the contents of the stomach become thoroughly liquefied, they pass into the duodenum, the first segment (about 10 inches [25 cm] long) of the small intestine. Most of our ingested vitamins and minerals are absorbed here.

Two ducts enter the duodenum:

- one draining the gall bladder and hence the liver

- the other draining the exocrine portion of the pancreas.

The liver secretes bile. Between meals it accumulates in the gall bladder. When food, especially when it contains fat, enters the duodenum, the release of the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) stimulates the gall bladder to contract and discharge its bile into the duodenum.

Bile contains:

- bile acids. These amphiphilic steroids emulsify ingested fat. The hydrophobic portion of the steroid dissolves in the fat while the negatively-charged side chain interacts with water molecules. The mutual repulsion of these negatively-charged droplets keeps them from coalescing. Thus large globules of fat (liquid at body temperature) are emulsified into tiny droplets (about 1 µm in diameter) that can be more easily digested and absorbed.

- bile pigments. These are the products of the breakdown of hemoglobin removed by the liver from old red blood cells. The brownish color of the bile pigments imparts the characteristic brown color of the feces.

The capillary beds of most tissues drain into veins that lead directly back to the heart. But blood draining the intestines is an exception. The veins draining the intestine lead to a second set of capillary beds in the liver. Here the liver removes many of the materials that were absorbed by the intestine:

- Glucose is removed and converted into glycogen.

- Other monosaccharides are removed and converted into glucose.

- Excess amino acids are removed and deaminated.

- The amino group is converted into urea.

- The residue can then enter the pathways of cellular respiration and be oxidized for energy.

- Many nonnutritive molecules, such as ingested drugs, are removed by the liver and, often, detoxified.

The liver serves as a gatekeeper between the intestines and the general circulation. It screens blood reaching it in the hepatic portal system so that its composition when it leaves will be close to normal for the body.

Furthermore, this homeostatic mechanism works both ways. When, for example, the concentration of glucose in the blood drops between meals, the liver releases more to the blood by

- converting its glycogen stores to glucose (glycogenolysis)

- converting certain amino acids into glucose (gluconeogenesis).

The pancreas consists of clusters of endocrine cells (the islets of Langerhans) and exocrine cells whose secretions drain into the duodenum.

Pancreatic fluid contains:

- sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3). This neutralizes the acidity of the fluid arriving from the stomach raising its pH to about 8.

- pancreatic amylase. This enzyme hydrolyzes starch into a mixture of maltose and glucose.

- pancreatic lipase. The enzyme hydrolyzes ingested fats into a mixture of fatty acids and monoglycerides. Its action is enhanced by the detergent effect of bile.

| In April 1999, the FDA approved orlistat as a treatment for obesity. Orlistat inactivates pancreatic lipase. About one-third of ingested fats fails to be broken down into absorbable fatty acids and monoglycerides and simply passes out in the feces. |

- 4 "zymogens" — proteins that are precursors to active proteases. These are immediately converted into the active proteolytic enzymes:

- trypsin. Trypsin cleaves peptide bonds on the C-terminal side of arginines and lysines.

- chymotrypsin. Chymotrypsin cuts on the C-terminal side of tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan residues (the same bonds as pepsin, whose action ceases when the NaHCO3 raises the pH of the intestinal contents).

- elastase. Elastase cuts peptide bonds next to small, uncharged side chains such as those of alanine and serine.

| Trypsin, chymotrypsin, and elastase are members of the family of serine proteases. Link to discussion. |

- carboxypeptidase. This enzyme removes, one by one, the amino acids at the C-terminal of peptides.

- nucleases. These hydrolyze ingested nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) into their component nucleotides.

The secretion of pancreatic fluid is controlled by two hormones:

- secretin, which mainly affects the release of sodium bicarbonate, and

- cholecystokinin (CCK), which stimulates the release of the digestive enzymes.

Digestion within the small intestine produces a mixture of disaccharides, peptides, fatty acids, and monoglycerides. The final digestion and absorption of these substances occurs in the villi, which line the inner surface of the small intestine.

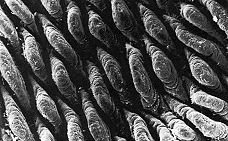

This scanning electron micrograph (courtesy of Keith R. Porter) shows the villi carpeting the inner surface of the small intestine.

| The crypts at the base of the villi contain stem cells that continuously divide by mitosis producing

- more stem cells

- Paneth cells, which secrete antimicrobial peptides [Link to discussion] that suppress the concentration of bacteria in the small intestine.

- cells that migrate up the surface of the villus while differentiating into

- columnar epithelial cells (the majority). They are responsible for digestion and absorption.

- goblet cells, which secrete mucus;

- endocrine cells, which secrete a variety of hormones;

|

The continuous production of new epithelial cells replace older cells that after about 5 days die by apoptosis.

The villi increase the surface area of the small intestine to many times what it would be if it were simply a tube with smooth walls. In addition, the apical (exposed) surface of the epithelial cells of each villus is covered with microvilli (also known as a "brush border"). Thanks largely to these, the total surface area of the intestine is approximately 40 square meters, some 20 times the surface area of the exterior of the body (~2 m2).

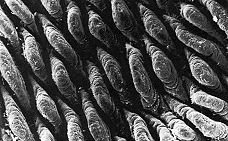

The electron micrograph (courtesy of Dr. Sam L. Clark) shows the microvilli of a mouse intestinal cell.

Incorporated in the plasma membrane of the microvilli are a number of enzymes that complete digestion:

- aminopeptidases attack the amino terminal (N-terminal) of peptides producing amino acids.

- disaccharidases These enzymes convert disaccharides into their monosaccharide subunits.

- maltase hydrolyzes maltose into glucose.

- sucrase hydrolyzes sucrose (common table sugar) into glucose and fructose.

- lactase hydrolyzes lactose (milk sugar) into glucose and galactose.

Fructose is converted into glucose in the villi, and both glucose and galactose are then transported to the liver in the hepatic portal vein.

- fatty acids and monoglycerides. These become resynthesized into fats as they enter the cells of the villus. The resulting chylomicrons — small droplets of fat and associated lipoproteins — are then discharged by exocytosis and pass into lymph vessels, called lacteals, draining the villi.

Humans with a rare genetic inability to form microvilli die of starvation.

The Large Intestine (colon)

The large intestine receives the liquid residue after digestion and absorption are complete. This residue consists mostly of water as well as any materials that were not digested.

The colon contains an enormous (~413) population of microorganisms. (Our bodies consist of about the same number (~313) of cells)

Most of the species live there perfectly harmlessly; that is, they are commensals. Some are actually beneficial, e.g.,

- by synthesizing vitamins, notably vitamin B12 and folic acid and

- by digesting polysaccharides for which we have no enzymes (providing an estimated 5-10% of the calories we acquire from our food).

Most of the bacteria belong to the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (although used as an indicator of water pollution by feces, E. coli is actually a minor component). In both obese mice (ob/ob) and humans, the relative proportion of Bacteroidetes declines and, in mice at least, the efficiency with which residual food is absorbed increases. Putting humans on a diet causes them to regain the normal proportion of Bacteroidetes. Why this relationships exists remains to be discovered.

Bacteria flourish to such an extent that as much as 50% of the dry weight of the feces may consist of bacterial cells.

Reabsorption of water is the chief function of the large intestine. The large amounts of water secreted into the stomach and small intestine by the various digestive glands must be reclaimed to avoid dehydration. If the large intestine becomes irritated, it may discharge its contents before water reabsorption is complete causing diarrhea. On the other hand, if the colon retains its contents too long, the fecal matter becomes dried out and compressed into hard masses causing constipation.

30 October 2018

The diagram shows the major topological relationships in the body. The linings of all

The diagram shows the major topological relationships in the body. The linings of all

Food placed in the mouth is

Food placed in the mouth is